Early

& Continuous Music

Lessons Improve Grades

Evelyn

Smith

M.S.

In Library Science, University of North Texas (2012)

Researchers hypothesize that the earlier a child start formal

music lessons the better. Indeed, educational psychologists have proven that it is best to begin formal training in playing a musical

instrument by age seven and keep it up through

the teenage years. Because musicians have to multi-task while they

are playing a musical instrument, this experience builds up

connections in different parts of their brain, starting at a very

young age. Of course, reading notes is similar to reading a language

since different notes represent different sounds. Thus, it comes as

no surprise that a child who learn to play an instrument early on

often shines in the classroom! However, waiting until a child is in

the third or fourth grade may be too late to reap all the benefits of

a music education.

"Music

learning supports all learning" since playing music forces a young

musician “to tap into multiple skill sets, often simultaneously”

(Brown, n. d., para. 2-3).

Early

music education, however, particularly benefits language development

since a child from age two to age nine is beginning to decode sounds

and words, and music reinforces these

skills (Brown, n. d., para. 5).

Learning

music develops the left side of the brain, which

processes language. Moreover, the relationship between music and

language development further develops social skills since

musical education strengthens verbal competency (Brown, n. d., para.

6-7).

For

example, in a University of Toronto study published in the 2004 issue

of Psychological Science, six-year-old children enrolled in either

voice or piano training scored three points higher on intelligence

tests than their peers who received drama training or acted as

controls. While the IQ's of the children taking drama classes did

not increase, they did improve their social behavior (Brown, n. d.,

para. 8-9).

Boston

College and Beth Israel Deaconess/ Harvard Medical School researchers

have also found that children who took 15 months of weekly music

instruction and practice improved their sound discrimination and

motor tasks as shown in the brain imaging of the regions of the brain

associated with these skills (Brown, n. d., para. 11). This is because a causal link between musical instruction and spatial

intelligence which helps students visualize how parts of a whole fit

together—a skill necessary for performing multiple-step math

problems (Brown, n. d., para. 12-13).

Furthermore,

elementary school students enrolled in superior music education

programs scored 22 percent higher in language and 20 percent high on

standardized tests than children who did not have this advantage

(Brown, n. d., para. 14).

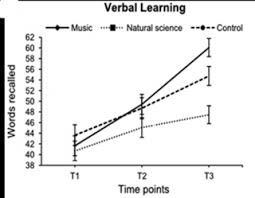

Although

schools with superior music and fine art teachers most probably also

have excellent teachers in other subject areas, musical training does

help with verbal recall (Brown, n. d., para. 15-16).

|

| Playing music makes kids happy. |

Practicing music also students be more self-disciplined, but in the end, it

keeps them “interested and happy” in school since a music

education helps children better understand themselves (Brown, n. d.,

para. 18-19).

So how does music teach verbal skills?

|

| Music improves grades and test scores. |

Butzlaff

argues that music can be used to teach for the following reasons:

Both

music and reading use written notation where a symbol indicates a

specific sound;

While

reading requires a sensitivity to phonological distinctions, music

requires a sensitivity to tonal distinctions;

When

students learn the lyrics of songs, they read a written text that is

often repetitive and predictable;

Joining

a school orchestra or band requires students to learn to work

together. Additionally, it puts pressure on each band or orchestra

member to be responsible and work hard.

(Butzlaff, 2000,

Autumn-Winter, Abstract, p. 167)

Costa-Giomi, E. (2004,

April). Effects of three years of piano instruction on children's

academic achievement, school performance and self esteem. Psychology

of Music,

32(2), 139-152. doi:10.1177/0305735604041491. [Abstract only].

Retrieved from http://pom.sagepub.com/content/32/2/139.short

When

63 Montreal four-graders received three years of free-of-charge

individual piano lessons and received an acoustic piano, at the end

of that period, they had better self-esteem and grades in music than

the 54 students that made up a control group, but this didn't affect

the grades they received in math and language arts when compared with

the controls (Costa-Giomi, 2004, April, Abstract, p. 139).

Fitzgerald, Kate F.

(2006, spring). The effect of instrumental music participation and

socioeconomic status on Ohio Fourth-, Sixth and Ninth-Grade

Proficiency Test Performance. Journal

of Research in Music Education,

54(1), 73-84. doi: 10.1177/002242940605400106. [Abstract only].

Retrieved from http://jrm.sagepub.com/content/54/1/73.short

Instrumental

music students out-performed non-instrumental students in every

subject and at every grade level, but since the youngest instrumental

music students had higher test scores than their peers, who were not

taking music, this suggested that public school instrumental music

programs simply attract better students at the onset. Interestingly

enough, however, lower-socioeconomic instrumental music students were

academically performing all other instrumental students by

ninth-grade (Fitzgerald, 2006, spring, Abstract, p. 73).

Teachers

often use calming, peaceful instrumental music in the classroom to

help students relax and focus (Gaddy, 2013, July 14, para. 2).

Moreover students who received early music instruction have a head

start in their studies since learning to play a musical instrument

improves fine motor skills, prompts memory, and boosts thinking

ability (Gaddy, 2013, July 14, para. 3). For example, research

studies have shown that young pupils who took piano lessons scored

higher in reading and math and had higher IQ's than their

non-music-taking controls (Gaddy, 2013, July 14, para. 4).

Moreover,

the National Association of Music Educators notes that students with

a musical background score 56 points higher on the verbal section of

the Sat and 39 points higher on the SAT math section than their

non-musical peers (Gaddy, 2013, July 14, para. 5). Instrumental

music students often outperform their counterparts in algebras

as well as excelling in reading, research, and writing (Gaddy, 2013,

July 14, para. 6). Music also improves memory skils whle relieving

stress and fatigue and boosting energy (Gaddy, 2013, July 14, para.

7-8).

Gaser

and Schlaug found more gray matter in the motor, auditory and

visual-spatial regions of the brain when comparing adult professional

keyboard players with amateur musicians and

non-musicians. They hypothesize that this represents adaptions in

response to long-term skill acquisition and repetitive rehearsals

(Gaser, 2003, October 8, Abstract, p. 9240).

While

listening to music can help students relax and concentrate, it does

not make students more intelligent. However, playing a musical

instrument does hone abilities such as speech perception the ability

to understand emotion in a voice, and multi-tasking (Hicks, 2014,

July 17, para. 5-6). Evidence also exists that playing a musical

instrument early in life improves math and reading skills (Hicks,

2014, July 17, para 19). This is because researchers have discovered

a connection between learning to play a musical instrument and

improved executive functioning, which includes such skills as problem

solving, the ability to switch tasks, and focus (Hicks, 2014, July

17, para. 21).

These

executive skills are perhaps enhanced since musicians use the

auditory motor emotional, and executive centers of the brain when

playing a musical instrument with a higher degree of precision than

is necessary when processing speech (Hicks, 2014, July 17, para. 32 &

34).

This

added practice, in turn, improves other learning processes since

there is an over lap because the brain networks that process music

also handles language, memory and attention (Hicks, 2014, July 17,

para. 33).

Additionally,

playing a musical instrument requires the musician to control

emotion, understand the importance of repetition and attention—all

of which promote brain plasticity (Hicks, 2014, July 17, para. 35).

Actual

classroom experience back these findings since early elementary

school students who have problems remembering the rhythm in musical

sequences also usually have problems in reading and math (Hicks,

2014, July 17, para. 4-45).

Hyde,

K. L., Lerch, J., and Norton, A. (2009, March 11). Musical training

shapes structural brain development. Journal

of Neuroscience,

29(10), pp. 3019-3025. [Full-text]. doi:

10:1523/NEURSCI.5118=08:2009. Retrieved from

http://www.jneurosci.org/content/29/10/3019.full

Just

15 months of instrumental musical training in early childhood

correlates with the enhancement of musically relevant motor and

auditory skills. Thus, researchers conjecture that similarly brain

malleability in adult musicians as well as experts in other fields is

most likely the result of training-induced brain plasticity” (Hyde,

2009,March 11, Abstract, p. 3019).

|

|

Make sure your teen keeps up music lessons through high school.

|

A

Quebec study finds that for every year high-performing high school

students in an International Baccalaureate program stayed in music

classes beyond their compulsory two years, their mean grades were

higher (Jacobs, 2013, August 26, para. 1-3). Nevertheless, these

results do not prove casualty since it is possible that these

students might otherwise be the smartest and most highly motivated

students in a highly-motivated set of students (Jacobs, 2013, August

26, para. 5).

Building

on a study in which six-year-old pupils who took voice or music

lessons did better than a control group who did not take music

lessons, E. Glenn Schellenberer argues that studying music initiates

a dose-response association in which the longer a child takes music

lessons, the higher his or her IQ and school grades will eventually

be (Munsey, 2006, June, para. 1-2 & 5). To obtain these results,

Schellenberger studied children age 6 through ll as well as university

freshman (Munsey, 2006, June, para. 6).

Accordingly

to Schellenberger for each additional month of music lesson a young

child takes, he or she increases his or her IQ By 1/6th

of a point, so six years of continuous music lessons would raise an

IQ by 7.5 points when compared with students who do not study

music (Munsey, 2006, Jun, para. 9). Moreover, university students who

spent six years playing music regularly increased their IQ's by two

points over their non-music playing university peers (Munsey, 2006,

June, para. 10).

Indeed,

Schellenberger argued that taking music lessons during childhood was

a “significant predicator” of a higher IQ in young adulthood

and higher grades while younger children who took music lessons are

more likely to make higher grades as well as higher scores on

achievement tests in math, spelling, and reading (Munsey, 2006, June,

para. 11).

Schellenberger

research indicates that after controlling for a student's family

income, parents' level of education, and the student's gender,

playing music regularly from kindergarten through high school

correlates with a “small but significant” bump in grades and

IQ (Munsey, 2006, June, para. 12).

Just

as the brains of older adults who had music lessons as children

respond faster than their counterparts who did not learn how to play

a musical instrument, formal musical traning also accelerates the

brain development in children since more areas of the brain are at

work when playing a musical instrument than when speaking (Music &

brain development, 2015, para 3-4).

Thus,

following these suggestions, parents should make music an important

part of their preschool and early-elementary school children's lives:

Expose

children to live and recorded musical performances as well as to

different styles and types of music;

Start

formal instruction in learning to play an instrument early;

Sing

with young children and play musical games with them;

Support

local music education programs.

(Music & brain

development, 2015, para. 5)

Piro,

J. M. and Ortiz, C. (2009, March 16). The effect of piano lessons on

the vocabulary and verbal sequencing skills of primary grade

students. Psychology

of Music,

37(3), pp. 325-347. doi: 10.1177/0305735608097248. [Abstract only].

Retrieved from http://pom.sagepub.com/content/37/3/325.short

When researchers

compared a group of 46 second-grade students who had formally studied

piano for three years with a control group of their peers who had no

formal musical instruction, they discovered that the students who

had taken piano lessons possessed “significantly better”

vocabulary and verbal sequencing skills (Piro, 2009, March 16,

Abstract, p. 325).

Research

has revealed differences in the brains of adult instrumental

musicians when compared with their non-musical controls since "musicians acquire and continually practice a variety of complex

motor, auditory, multiple-modal skills." Similarly, early

instrumental training in children improves their long-term visual,

spatial, verbal, and mathematical performances (Schlaug, 2005,

December, Abstract, p. 219).

Steele,

C. J., Bailey, J. A. and Zatorre, R. J., et

al.

(2013, January 16). Early musical training and white-matter

plasticity in the corpus

callosum: Evidence

for a sensitive period.

Journal of Neuroscience,

3(3), pp. 1282-1290.

doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3578-12.2013. [Full text]. Retrieved from

http://www.jneurosci.org/content/33/3/1282.full

When

Concordia University, McGill University, and Max Planck Institute

researchers compared the white-matter organization in the brains of

early and late-trained musicians matched for years and experience,

they found that those musicians that formally studied music before

age seven possessed "greater connectivity" in the region of the

brain related to sensory motor synchronization experience. The

researchers posit that early musical training results in more

white matter connectivity, which will, in turn, serve as a scaffold

on which to build future skills (Steele, 2013, January 16, Abstract).

The

researchers reached this conclusion after testing 36 musicians,

dividing them into two groups, those who began formal training

before age seven and those who started later. All of the musicians

had at least seven years of formal musical training and were either

enrolled in a university music program or were performing

professionals. The researchers then compared these two groups to

six controls, who did play music (Steele, 2013, January 16, para. 6).

All

participants then completed a motor sequencing task, synchronizing a

ten-element sequence of short and long visual cues that formed a

temporal sequence or rhythm by tapping out the beats (Steele, 2013,

January 16, para. 7).

Researchers

theorized that playing a musical instrument necessitates hand

coordination with inter-hemispheric interaction—a task that

requires bi-manual skills. This places more demands on

inter-hemispheric interactions between sensory-motor regions at a

critical time in life for learning music (Steele, 2013, January 16,

para. 26).

Wan,

C. Y. and Schlaug, G. (2010, October). Music making as a tool for

promoting brain plasticity across the life span. The Neuroscientist,

16(5), pp. 566-577. doi: 10.1177/1073858410377805. [Full text].

Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2996135/

Musicians

learn and repeatedly practice motor actions that cause specific sound

and visual patterns while receiving constant and immediate feedback

on their performance. This combination of factions strengthens the

connections between the auditory and motor regions of the brain while

activating the region of the brain that integrates these various

skills. Wan and Schlaug therefore argue that the training of this

neural network also heightens other cognitive skills and behavioral

reactions (Wan, 2010, October, Abstract, p. 566).

Some

musical beats encourage critical thinking and develop math concepts (2013, August 30, para. 1).

Organized

Music

Since

taking music lessons for a longer period of time increases their

effect, teens should continue to take music lessons as long as

possible, for doing so will increase their chances of making better

grades (White, 2013, August 30, para. 2).

Background

Music

Playing [instrumental]

music in the background while studying may help students feel more

comfortable; and if they are studying in a group, music creates a

“privacy barrier” that helps some student more willing to

contribute (White, 2013, August 30, para. 3).

__________

Musical

Training Starts in

|

|

Kids need to be a part of music.

|

Starting

in nursery-school, children can benefit from exposure to music if

they participate in making it—singing songs with hand motions,

moving their bodies to the beat, and playing in a rhythm band.

However, listening to music at this stage can be important too since

it can either energize the children or put them to sleep. Music also

helps children diagnosed autism spectrum disorder to concentrate and

better relate to others.

Incorporating

music into early childhood experiences enhances children's ability to

learn, sharpens their mental focus, and adds to a “sensory-rich”

environment that promotes the development of neural pathways

(Chaloux, 2016, para. 1).

Actively

Experience

Preschoolers

and early elementary school students respond best to music when they

actively participate in making it. Accordingly, show them how to

move to both slow and fast-moving beats and then use different tempos

to help them build their listening skills. Also, sing songs together that include hand

motions and finger plays since combing music and movement helps

children coordinate and control body movements while they develop

self-control and learn to concentrate (Chaloux, 2016, para. 2).

Academic

Concepts

Teach

academic concepts like the alphabet, counting, and the multiplication

tables through music, handing out tambourines, shakers, and drums to

have children tap to a beat. This incidentally builds auditory

discrimination, which helps children learn to sound out words. Sing

together a variety of song to build vocabulary and language skills,

and help them learn to recognize mathematical pattern and reasoning

skills by having them tap and clap out a rhythm (Chaloux, 2016, para.

3).

Comfort

Children

often use music to comfort and soothe themselves, so incorporate

music into their daily routines; for example, singing songs on the

way to a new school to ease their anxiety, humming a lullaby at

bedtime to lull them to sleep, or popping an appropriate CD into the

CD player to spur them to clean up their toys (Chaloux, 2016, para.

4).

Expose

children to different genres and styles of music, like classical,

folk, and jazz, while incorporating singing, dance, and music into many

of their daily activities. Checking out music CD's at the public

library [as well as playing previewed and age-appropriate YouTube

videos] are free-of-charge ways to expose young children to music

(Chaloux, 2016, para. 5).

Gruhn separated twelve

urban, upper middle class German one- and two- year-old children into

experimental and control groups, and for the next 15 months, the

children in the control group had no exposure to music apart from the

songs sung in a local daycare program while the children in the

experimental group were place in a stimulating musical environment.

At the end of this period, the control group's body movements and

vocal performance were significantly less developed than their

experimental counterparts, who showed more adroit motor co-ordination

and voiced more sophisticated tonal and rhythm patterns (Gruhn, 2002,

Abstract, p. 51).