Evelyn E. Smith

M.S. in Library Science, University of North Texas, 2012

Ph. D. in English (Contemporary and 19th-century Fiction & Rhetoric),

Texas Christian University, 1995

Revised December 15, 2014

Revised December 15, 2014

Taking a census of American readers furnishes some intriguing information: E-book readers consume 24 books annually while

non-e-book readers read only 15. However, adults over 18 on average

read 17 books per year, according to the latest survey available (Delaware, 2012, August 5). Even so, one in four adults read no books at

all last year, and those who did read were women and older adults who

were more likely to read religious works or popular fiction (Fram, 2007, August 2, para. 2-3). Hence,

providing a blog on both religious works as well as Christian fiction

answers a real need.

Unfortunately however “the vast majority of what passes

for Christian literature is banal, poorly written, dull as tears and

message driven” (Christian fiction as propaganda, 2014, October 1, para. 2). This

is perhaps because Christian publishers currently judge submissions not

on their literary merit or commercial success but instead select works that support a particular doctrine or message (Christian fiction as propaganda, 2014, October 1, para. 4).

Consequently, this blog is geared not only to readers who are drawn to works that have real literary merit, such as C. S. Lewis's Cosmic

Trilogy--Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandria (1944), and That Hideous Strength (1945)--and Elizabeth Speare's controversial, Newbery

Award winning children's novel, The Bronze Bow (1961), but also to the all the more typical Christian bestsellers like

Kay Arthur's Israel, My Beloved (1996) or novels like Douglas Bond's Betrayal or Michael Giesler's Grain of Wheat that fulfill an indoctrination or educational need. Finally, the reader should compare these novels with Frank E. Peretti's Piercing the Darkness, which while aimed at an evangelical audience clearly also appeals to readers of suspense novels and Angela Hunt's The Debt, which easily also fits into the chick lit genre.

All of the novels reviewed on this blog page are available either as e-books free-of-charge online, or at a nearby public library, or through Interlibrary Loan (http://WorldCat.org/). All of which resulted in asking a final, as yet, unanswerable question: If authors write Christian novels as a way of spreading the gospel, or good news, of salvation, why isn't all Christian fiction eventually available in e-book format as well as in print?

References

All of the novels reviewed on this blog page are available either as e-books free-of-charge online, or at a nearby public library, or through Interlibrary Loan (http://WorldCat.org/). All of which resulted in asking a final, as yet, unanswerable question: If authors write Christian novels as a way of spreading the gospel, or good news, of salvation, why isn't all Christian fiction eventually available in e-book format as well as in print?

References

Christian fiction as propaganda.

(2014, October 1). The Willow Branch. Word Press.

Retrieved from

https://aurorawatcherak.wordpress.com/2014/10/01/christian-fiction-as-propaganda/

Fram, Alan. (2007, August 21). One in

four read no books last year. The Washington Post.

Q. How many books does the average

American read a year? Divison of Libraries' Blog. State of Delaware.

http://library.blogs.delaware.gov/2012/08/05/q-how-many-books-does-the-average-american-read-a-year/

lll

Arthur, Kay. (1996). Israel My

Beloved: A Historical Novel. Reprint 2001. Eugene, Oregon:

Harvest House Publishers. Published only in English [print, e-book through Interlibrary Loan

(ILL), e-book online free-of-charge online]. Genre Category: Christian Fiction,

Jewish Fiction, and Historical Fiction.

Arthur's epic novel traces the story of

the Jewish people from their beginnings to the present day by using

the character of Sarah as an allegory. However, sweeping the tale

might be, the reader might be tempted to put down this didactic

novel.

|

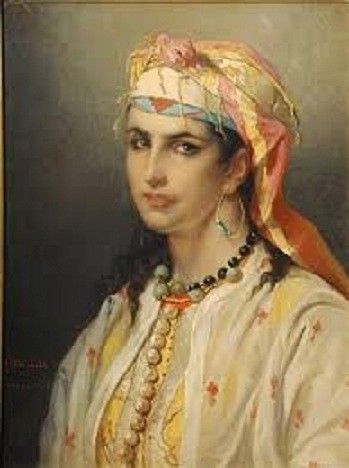

Arthur's "Sarah" serves as

an allegory for Israel.

|

This novel is available as a free

download through Word Press:

http://freedownloadiisraelmybeloved.wordpress.com/2014/04/14/israel-my-beloved-free-download/

The first chapter of Arthur's novel is

also available through Precept:

Israel My Beloved. (2014).

Goodreads. Retrieved from

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/6155.Israel_My_Beloved

This epic, historical novel quickly

rose to the top of the Christian hardcover fiction lists, so

Goodreads Community Reviews give it a rating of 4.16, praising

this retelling of the story of the Jewish people in novel form as Kay

Arthur personifies the nation of Israel in the character of Sarah

from the time of the Babylon Captivity through the Diaspora, the

Holocaust, and the coming of the Messiah. Even so, as some reviewers

admit, readers may have trouble adjusting to the allegorical format.

Bond, Douglas. (2009). The Betrayal:

A Novel on John Calvin. Phillipsburg, New Jersey: P & R

Publishing Company. Published only in English [print only]. Genre Category: Christian Fiction,

Historical Fiction (hagiography), and Young Adult Fiction.

Beginning with John Calvin's 500th birthday in 2009, American Presbyterians have become increasingly aware of the origin of their denomination. Hence, they and other Protestants might be interested in Douglas Bond''s historical novel, which summarizes some of the major tenets of Reformed Protestantism.

WorldCat furnishes reviews from

Goodreads as well as nearby libraries that have the novel on

their shelves:

http://www.worldcat.org/title/betrayal-a-novel-on-john-calvin/oclc/318100547

The Betrayal: A Novel on John

Calvin. (2014). Christian Liberty. Retrieved from

http://www.shopchristianliberty.com/the-betrayal-a-novel-on-john-calvin

Calvin's fictional rival narrates a

fast-paced story that also gives a broad overview of the Reformation

as well as Calvin's systematic theology in a novel aimed at young

adult readers.

The Betrayal: A Novel on John

Calvin. (2014). Goodreads. Retrieved from

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/6485597-the-betrayal

Twenty Goodreads reviewers gave

Bond's hagiographic novel on John Calvin a 4.05 rating. Readers,

however, should be cautioned that the central character in the novel

isn't one of the founders of the Reformation, but rather his envious

valet, who becomes an informer who betrays the meeting places of

Protestants to the French Crown. The novel contains some

anachronisms, but most readers applaud the author's research since it

paraphrases most of the tenets of reformed Protestantism. Some

reviewers, however, find the tale too pedantic.

Dykstra, Jon. (2008, June). The

Betrayal: A Novel on John Calvin. Reformed Perspective.

Retrieved from

http://reformedperspective.ca/index.php/book-reviews/237-the-betrayal-a-novel-on-john-calvin?catid=41%3Anovels-etc

Dykstra finds The Betrayal “a

fascinating read, but one that takes some effort” since “the

weighty theological dialogues . . . make this [Young Adult] novel

best suited for adult Calvin enthusiasts” (Dystra, 2008, para.

1-2).

Meyers, Amy. (2014). The Betrayal:

A Novel. Ita Vita: Such Is Life in Africa. Retrieved

from

Meyers find The Betrayal more

entertaining than John Calvin's Institutes of the Christian

Religion, although its documented index contains references to

Calvin's writings, even if few passages directly address

predestination, election, and free will (Meyers, 2014, para. 8-9).

Meyers, nevertheless, finds that some of the most riveting passages in

the novel require a willing suspension of disbelief, such as the

narrator's hitching a ride to Paris on the bottom of Calvin's

carriage (Meyers, 2014, para. 3 & 14). Meyers' thoughtful

analysis serves as an excellent guide to Bond's novel.

Giesler, Michael Edward. (2008). Grain

of Wheat: A Novel. New Rochelle, New York: Scepter Publishing

Company. Published in English and Spanish [print only]. Genre Category: Christian Fiction,

Historical Fiction, and Young Adult Fiction.

Father Michael Giesler's story of

Marcus, the son of a distinguished Roman senator who uses rhetorical

skills as a philosopher to defend his faith in second-century Rome,

focuses on the daily struggles that early Christians faced as they

were disowned by their families and turned in to the authorities.

Marcus never denies his faith in contrast to an apostate friend, so like his sister Junia in an earlier Giesler novel, he is martyred

for his faith. The novel, nevertheless, brings up more questions

than it answers, awakening in the reader the wish to know more about

the differences between Gnosticism and traditional Christianity,

exactly when Christians first started to venerate the Virgin Mary,

and the role of women in house churches. The novel's title, Grain of

Wheat, refers to the parable of the wheat and the tares found in

Matthew 13: 24-30

|

Grain of Wheat explores the lives

of early Christian martyrs.

|

Edgecomb, Kevin P. (2008, October 11).

Grain of Wheat. Biblicalia. Retrieved from

http://www.bombaxo.com/blog/grain-of-wheat/

Grain of Wheat is the third

installment in a trilogy that follows the lives of early Christians

in Rome, specifically centering around the story of the son of a

senator and the results of his conversion on his family (Edgecomb,

2008, para. 1). Edgecomb praises Giesler for his ability to convey

the anxiety these felt by these potential Christian martyrs who lived

in fear that their outlawed faith might be discovered by the Roman

authorities in this Young Adult novel (2008, para. 2 & 3).

Were the Early Christians

Counter-Cultural. [Interview with Father Michael Giesler]. (2014).

Catholic Answers. Retrieved from

http://www.catholic.com/radio/shows/were-the-early-christians-counter-cultural-encore-3878

Audio interview with Father Michael

Giesler, a priest of Opus Dei, a member of the Fellowship of

Catholic Scholars, and a Senior Fellow of the St. Paul Center for

Biblical Theology, and author of a trilogy focusing on a Roman

family that lives about 140 CE.

Grain of Wheat. (2014).

Goodreads. Retrieved from

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/6081400-grain-of-wheat

Readers give this fictional depiction

of second-century Roman Christians a 4.32 rating.

Hunt, Angela. (2004). The Debt:

The Story of a Past Redeemed. Nashville, Tennessee: Westbow. Published only in English [large print available; no e-book]. Genre Category: Christian Fiction and Chick Lit.

The Debt calls into question the

idea that Christians should spend all their time in church, for they

can't truly serve Christ if they don't meet the needs of sinners.

Thus, repentant sinners might be the best witnesses. Certainly, Emma

Rose Howard, the fallen woman turned televangelist's wife,

experiences a personal reawakening after the son she gave up as an

unwed mother contacts her.

|

Hunt takes her inspiration

for The Debt from Luke 7:36-50.

|

The Debt Discussion Questions by

Angela Elwell Hunt. (2014). Christianbook.com. Retrieved from

http://www.christianbook.com/Christian/Books/cms_content?page=660212&sp=74424

Hunt intends The Debt to serve

as an allegory illustrating the parable Jesus told in response to a

Pharisee's self-righteous response when a sinful woman anoints Him

with a costly perfume in Luke 7:36-50:

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Luke+7%3A36-50&version=NIV

Goodreads reviewers gave this

easy-to-read, thought-proving first-person narrative a 4. 05 rating.

In The Debt, the wife of a televangelist must confront her hidden

past as well as discover that Christian ministry must extend beyond

the premises of the church building.

Jess. (2011, February 9). Brook

Review—The Debt by Angela Hunt. In Christ Alone Family.

Retrieved from

http://www.inchristalonefamily.com/2011/02/book-review-debt-by-angela-hunt.html

Jess writes, “If you feel like you

are 'playing church' and not following the footsteps of Jesus, I

urge you to read this book.”

Lewis, C. S. (1938). Out of the

Silent Planet. New York Scribner. Published in English, French, Italian, and Swedish [print, e-book available

through ILL]. Genre Category: Christian Fiction and Science Fiction.

The first book in C. S. Lewis's* Space or Cosmic Trilogy, Out of

the Silent Planet answers the question of what kind of society

would exist if man's fall from grace had never occurred.

“Note: Purdue University's Online Writing Lab recommends adding an

extra s after an apostrophe in a single noun even if it ends in s;

for example, James's epistle.

(https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/621/01/).

| C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien each challenged each other to write a work of science fiction, so Lewis penned Out of the Silent Planet. |

Cohen, Tal. (1999, February 26). Out

of the Silent Planet/ C. S. Lewis. Tal Cohen's Bookshelf.

Retrieved from http://tal.forum2.org/cosmic1

Even though Out of the Silent Planet's

plot is similar to the plots of many pulp science fiction novels

published during the 1930s, it's “loaded with Christian symbolism

in references” (Cohen, 1999, para. 4). Cohen finds this

suspenseful science fiction classic “enjoyable and easy to read” even if the

characters are “somewhat lacking”. For example, Professor Weston

is the “stock evil professor” (1999, para. 5).

Folks, Jeffrey. (2003, spring). Telos

and existence: Ethics in C. S. Lewis's space trilogy** and Flannery

O'Connor's Everything That Rise Must Converge. The

Southern Literary Journal, 35(2) 107-118. doi:

10.1353/slj.2003.0019. Project Muse. Retrieved from

http://mtw160-198.ippl.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/southern_literary_journal/v035/35.2folks.pdf

**Critics refer to Lewis's three science fiction novel as both his

“space trilogy” and his “cosmic trilogy: since he sets That

Hideous Strength in England.

Both Lewis and O'Connor believed that

society is “innately corrupt”, so a humanist approach to ethics

would “devolve into self-interest”. Accordingly, they wrote as

antagonists of twentieth-century secular humanism since they believed

that at least some of their audience would not necessarily have any

faith in “orthodox Christian dogma'” (p. 107).

Gosling, John. (2013, January 1). Out

of the Silent Planet by C. S. Lewis (1938). War of the Worlds

Invasion: The Historical Perspective. Retrieved from

http://www.war-ofthe-worlds.co.uk/out_of_the_silent_planet.htm

Gosling admits that “Lewis

has a predilection to lace his fiction with Christian references”in this “well-written and important piece of Martian Science

Fiction”, but whether or not this interferes with the telling of the

tale is “entirely in the eye of the beholder” (Gosling, 2013,

para. 1).

Von Ruff, Al. (2014, August 5). Lewis,

C. S The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved from

http://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/lewis_c_s

Both Out of a Silent Planet and

Perelandria are planetary romances with elements of medieval

mythology as evidenced by Elwin Ransom's surname. Although Lewis today is known primarily as a Christian apologist, he was a professor of medieval and renaissance literature, and one of his best known scholarly works. Allegory of Love (1936), explored the use of allegory in medieval romance poetry. In turn, he used this expertise in his own works of fiction.

|

| Artists envision Perelandria. |

Lewis, C. S. (1944). Perelandra: A

Novel. New York: Scribner. [Published in English and Swedish [print, and audio e-book available through ILL,

e-book available online free-of-charge]. Genre Category: Christian

Fiction and Historical Fiction.

Elwin Ransom, the protagonist in both

Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandria must prevent

the Green Lady from sinning by persuading her that obedience to God

is preferable to disobeying the single law that He has decreed,

prohibiting Perelandria's Lady from staying the night on the

fixed lands.

Cohen, Tal. (1999, February 26).

Perelandria/C. S Lewis. Tal Cohen's Bookshelf.

Retrieved from http://tal.forum2.org/cosmic2

Neither a horror novel, nor a work of

science fiction, Perelandria serves puts into fictional form the a debate about faith and obedience: Dr. Weston, the evil physicist who first appears

in Out of a Silent Planet, takes on the role of the tempter, urging a

Venus Eve to sin, while Ransoms argues Heaven's case for obedience to God (Cohen, 1999

para. 4-6). However, Cohen is surprised by Ransom's “non-Christian”

solution to this problem (1999, para. 10).

Inglish, Patty. (2014). Perelandria.

Education. About.com. Retrieved from

http://classiclit.about.com/od/perelandracslewis/fr/aa_perelandra.htm

Inglish summarizes the Perelandria

installment in Lewis' Cosmic Trilogy, which she believes “will

surely attract Star Trek fans of Vulcans and green dancing girls

(2014, para. 10).

McCormick, Judith Kay. (1972, August).

Christianity on Venus: A Study of Allegorical Meaning in C. S. Lewis'

Perelandria. M. A. Thesis. Texas Tech University. Retrieved

from

Like C. S. Lewis's

literary criticism, his fiction uses analogy, metaphor, and simile to

present abstract ideas. Thus, while Perelandria may appear didactic, this isn't the fault of the allegorical elements within the

novel. Rather it is the result of Ransom's reflections during which

he muses on the meaning of an episode (McCormick, 1972, p. p. 1 &

3).

Perelandria. (2014). Bookrags.

Retrieved from http://www.bookrags.com/Perelandra/#gsc.tab=0

Bookrags downloads include study

guides and lesson plans.

Von Ruff, Al. (2014, August 24).

Bibliography: Perelandra. Internet Speculative Fiction

Database. Retrieved from

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?1401

Von Ruff lists Perelandria's

publication history and reviews.

Wikipedia again provides a plot summary

of Lewis' fictional take on his “A Preface to Paradise Lost” in

which he deals with “the value of hierarchy, Satan's dullness, and

unfallen sexuality” (Wikipedia, 2014, para. 14).

Lewis, C. S. (1945). That Hideous

Strength: A Modern Fairy Tale for Grown-Ups. Reprinted

1996. Scribner Classics. Published in English, Czech, and Spanish [print, e-book available through ILL].

Genre Category: Christian Fiction and Science Fiction.

C. S. Lewis continues to argue in favor

of obedience to hierarchical authority as a prerequisite to living a

Christian life rather than adopting the adhering to the moral

relativism of humanism as he juxtaposes the experiences of a wife who

surrenders her will to Maledil, or Jesus Christ, and a husband who

comes to learn that seeking only success is never the goal of a

purpose-driven life.

|

That Hideous Strength inspires art exhibits:

|

Bullad,

Sadie H. (2011, spring/summer). Narrative dualism in C. S. Lewis's

That Hideous Strength. Mytholore, 29(3/4),

pp. 11-24 Retrieved from

https://harding.edu/assets/english/pdf/bullard.pdf

Even though C. S. Lewis rejects

philosophical dualism, he successfully employs narrative dualism as a

literary device in That Hideous Strength as the separate

experiences of Mark and Jane Studdock to a unity of purpose and

marital harmony by novel's end (Bullard, 2011, p. 11).

- N.I.C.E., a sinister research institution controlled by an evil spirit found in a decapitated head, employs Mark in order to gain control of Jane's prophetic abilities while Jane joins a Christian commune that follows the orders of Maledil, so she comes to serve a higher purpose (Bullard, 2011, p. p. 12-13).

- Jane can't fully commit to her marriage while Mark commits to the N.I.C.E. Organization for all the wrong reasons: As a newly married man, he wants a raise to support his wife, but he comes to understand that more importantly marriage requires giving a partner emotional support (Bullard, 2011, p. p.13-14).

- Lewis bequeaths opposing concepts of femininity to each camp: Logres at St. Anne's is a place of beauty and warmth while the N.I.C.E. Headquarters at Belbury is a :”cold” place (Bullard, 2011, p. 15-16).

- The initiates at both St. Anne's and Belbury have a different concept of death: The St. Anne commune accepts death as “a purposeful and sacred element of life” while the initiates at Belbery hang onto life “at any cost” (Bullard, 2011, para. 16).

- The rooms where the initiates become full-fledged members of each group give off either a good or evil atmosphere: The blue room at Anne Anne where Ransom stays gives off an aura of serenity and comfort while the Objective Room at N.I.C.E. Headquarters dehumanizes those it inducts (Bullard, 2011, p. 17).

- Mark stays at Belbury, and Jane stays at St. Anne's for different reasons: She chooses to stay out of her own free will while the chief of N.I.C.E.'s police, Miss Hardcastle, coerces Mark to stay after he is framed for Hingest's death (Bullard, 2011, p. p. 19-20).

- Merlin's stay at St. Anne's and the tramps time at N.I.C.E. Headquarters result from the orders of the leader of each group: Ransom creates in his followers a total sense of commitment to their causes, while the evil spirit that inhabits thehead of a decapitated criminal at Belbury relies on fear: Mark can't be fully driven from N.I.C.E. Headquarters until he is forced to flee for his life even as he “begins to see through the charades of the inner circle” (Bullard, 2011, p. p. 21-22).

Cohen, Tal. (1999, February 26). That

Hideous Strength/ C. S Lewis. Tal Cohen's Bookshelf.

Retrieved from http://tal.forum2.org/cosmic3

Cohen finds That Hideous Strength

the most readable book of Lewis' Cosmic Trilogy and lauds the plot as

“highly absorbing and “almost a page turner”--a viewpoint hotly

contested by many of the replies to his review (1999, para. 2). He

also applauds the well-developed characters of the novel's main

protagonists, Jane and Mark Studdock, while he again finds the evil

characters “rather flat” and the novel “lacking in depth”

(Cohen, 1999, para. 5-7). Replies to Cohen's review, however, see

That Hideous Strength as Lewis' attack on moral

relativism and trans-humanism.

Inglish, Patty. (2014). That

Hideous Strength. Education. About.com.

Retrieved from

http://classiclit.about.com/od/thathideousstrength/fr/aa_thathideous.htm

Inglish praises

That Hideous Strength as an exciting science fiction story

that echoes the message of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932) and

possibly influences George Orwell's dystopian classic 1984 (1949)

since N.I.C.E.'s humanist attempt to “cure”social and genetic

problems “dissolves into unintelligent babbling” in this

indictment of Communism and socialism (Inglish, 2014, para. 1-2 &

9 & 13).

Johngo. (2004,

January 10). That Hideous Strength. A long pretentious

review. E-pinions. Retrieved from

http://www.epinions.com/review/That_Hideous_Strength_by_C_S_Lewis/content_122485247620?sb=1

Johngo finds That

Hideous Strength a “thought-provoking allegory”, although he

criticizes Lewis' conservative (or perhaps reactionary) attitude

about the proper roles of men and women in society. Bottom Line:

For this anonymous reviewer, the final installment of Lewis' space

trilogy is “Tolkien for grownups who prefers novels to romances”

(Johngo, 2004, para. 1).

Johngo also pegs

Lewis as a reactionary, protesting the rise of science in British

universities during the 1930s and 1940s along with the accompanying

declining influence of the arts. Thus, Lewis cares even less about

sociology than the other sciences and accordingly disparages Mark

Studdock as a “modern man whose education is neither scientific or

classic” and whose only goal in life is success (Johngo, 2004,

para. 14-15). At the same time, however, Lewis takes a not-so-subtle

dig at Jane Studdock's unimaginative dissertation topic—John

Donne's “triumphant vindication of the body”(Johngo, 2004, para.

8). As opposed to the evolutionist point of view, both Lewis and

Tolkien maintained an Elizabethan or metaphysical worldview, hence

they see the rise of science as a product of the fall from grace

(Johngo, 2004, para. 30).

Orwell, George.

(1945, August 16). The scientists take over. Manchester Evening

News. Reprinted in The Complete Works of George Orwell.

(1998). ed. Peter Davison.18, 2720 (first half), p.p. 250-251.

Retrieved from http://www.lewisiana.nl/orwell/

Orwell sees That

Hideous Strength as essentially a crime story, whose menancing

tone Lewis has borrowed from G. K. Chesterton's metaphysical

thriller, The Man Who Was Thursday (1908). Hence, the plot

would be better without the extraneous miraculous elements (1945,

para. 1-3). Orwell sees the novel as a struggle against a group of

“mad scientists” who have set out to conquer Britain and

ultimately the world (1945, para. 4).

Scakel, Peter.

(2014, February). That Hideous Strength. Encyclopaedia

Britannica. Retrieved from

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/590081/That-Hideous-Strength

Although the

protagonist in the first two books of Lewis' Cosmic Trilogy, Elwin

Ransom, remains a pivotal character in That Hideous Strength,

his role in the action remains very limited. Instead the action focuses on

a minor researcher, Mark Studdock, who falls under the influence of

N.I.C.E., a sinister think tank, so as to gain control of Jane, his

wife, who suffers from prophetic but terrifying dreams. Therefore,

while Mark finds himself in the clutches of N.I.C.E., Jane

experiences a conversion experience when as a refuge she is taken in

by the Christian commune that has organized itself around Ransom

(Scakel, 2014, 1-3). N.I.C.E.'s attempt to gain totalitarian control

of England puts into fictional form the themes Lewis explored in The

Abolition of Man (1943) and foreshadows George Orwell's 1984

(1949) (Schakel, 2014, para. 1).

Smalt, Jonathan. (2014)."Scientism, Satire, and

Sacrificial Ceremony in Dostoevsky's “Notes From

Underground”and C. S. Lewis's “That Hideous Strength”

Masters Theses. Paper 321. Liberty University.

Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/masters/321

Both Fyodor Dostoevsky and C. S. Lewis use satire, exaggeration, and wit to demonstrate the absurdity of a worldview built upon the naturalist philosophy of science (Smalt, 2014, Abstract).

Both Fyodor Dostoevsky and C. S. Lewis use satire, exaggeration, and wit to demonstrate the absurdity of a worldview built upon the naturalist philosophy of science (Smalt, 2014, Abstract).

That Hideous Strength summary.

(2014). Bookrags. Retrieved from

http://www.bookrags.com/That_Hideous_Strength/#gsc.tab=0

Users can download

a study guide and lesson plans for That Hideous Strength, a

dystopian novel that stands on its own but can be read as part of a

science fiction trilogy.

That Hideous Strength. (2011,

March 26). ebook3000.com. Retrieved from

Ebook 3000 furnishes

a free e-book download of C. S. Lewis's That Hideous

Strength.

That Hideous

Strength (Space Trilogy # 3). (2014). Goodreads.

Retrieved from

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/100933.That_Hideous_Strength

While some

reviewers label That Hideous Strength a satiric masterpiece,

others criticize Lewis' stance on feminism. Mark Studdock is a

sociologist “enticed” to join N.I.C.E., a sinister organization

that attempts to control all human life, Jane, his wife, find

consolation for her disturbing prophetic dreams at St. Anne's a

company of Christians that his formed around the Dr. Ransom of the

first two novel's in Lewis' Cosmic Trilogy.

That Hideous Strength. (2014,

July 23). Wikipedia. Retrieved from

Wikipedia provides a summary of

That Hideous Strength as well as its context, characters,

philosophy, reception, publication history and its place in popular

culture. Fellow Inkling Charles Williams and Science Fiction novelist

Olaf Stapledorf heavily influenced this dystopian novel, although

Lewis' fictionalizes the theme of his Abolition of Man (1943),

arguing in favor of natural laws and objective values (Wikipedia,

2014, para. 2-3).

Tubbs, Mark. (2008, December 2). That

Hideous Strength: A Modern Fairy Tale for Grown-ups. Discerning

Reader. Retrieved from

http://discerningreader.com/book-reviews/that-hideous-strength

Tubbs recommends That Hideous Strength

as a “one-of-a kind, dualistic novel in which the Lamb wins, but

not in the way you might expect”, classifying it as an “enjoyable”

and “eccentric” “modern classic”, rich in themes and

allusions (2008, para. 1-2). Tubbs also notes that That Hideous

Strength resembles George Orwell's 1984 (1949), G. K.

Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday (1908), Aldous Huxley's

Brave New World (1932), and Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent

(1907), although these novels lack That Hideous Strength's

supernatural elements (2008, para. 3).

Wajenberg, Earl. (2011). Summary of

That Hideous Strength by C. S. Lewis. Retrieved from

Wajenberg summarizes That Hideous

Strength in detail while offering little actual criticism of the

third book in C. S. Lewis' Cosmic Trilogy, which Wajenberg

characterizes as “longer and more intricate” than Out of the

Silent Planet and Perelandria (2011,

para. 1). Wajenberg

also notes that the plot centers around Mark Studdock, a research

fellow, and his wife Jane, a Donne scholar, living in an imaginary

English university town following World War II rather than around the previous protagonist of Lewis's other novels in the Cosmic Trilogy,

Elwin Ransom (a. k. a. Mr. Fisher-King), who only occupies a small

role in the action, although a company of Christian organizes itself

around his leadership (2011, para. 3-5 & 44).

Peretti, Frank E. (1989). Piercing

the Darkness. Westchester, Illinois: Crossway Books. Published in English, Hungarian, Polish, and Spanish [print, large print, audio-e-book; e-book also available through Google]. [Genre Category:

Christian Fiction, Suspense, and Fantasy].

Evangelical Christians use the power

of prayer to oppose New Age spiritualism, contemporary educational

theory and practice, and demonic possession in a supernatural

page-turner as Peretti brings new meaning to the phrase, “the devil

made me do it”.

Piercing the

Darkness. (2014). Christianbook.com. Retrieved from

http://www.christianbook.com/piercing-the-darkness-frank-peretti/9781581345278/pd/45271

Readers

in Peretti's target audience give Piercing the Darkness

a 4.9 out of 5 rating, noting that it literally opened their eyes to

the spiritual realm; or else, it figuratively exposed them to the use

of angels and demons as an allegorical literary device.

Piercing the Darkness (Darkness

#2). (2014). Goodreads. Retrieved from

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/17303.Piercing_the_Darkness

Theologians criticize Peretti's concept

of territorial angels summoned by prayer.

|

Goodreads reviewers give

Piercing the Darkness a 3.27, most readers finding it a

readable book filled with “effective suspense” and “an

inventive narrative structure, even if this “supernatural

page-turner” is also full of stereotyping from an evangelical,

conservative perspective.

Piercing the Darkness. (2012,

December 2). Wikipedia. Retrieved from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piercing_the_Darkness

This sequel to Frank Peretti's This

Present Darkness (1988) won the Evangelical Christian Publishers

Association (ECPA) Medallion Book Award for Best Fiction for 1990,

thus further promoting a belief in territorial spirits and spiritual

warfare (Wikipedia, 2012, para. 1). The story interweaves two

plots as a former New Age cult member, Sally Beth Roe attempts to

escape her past while ferreting out the truth behind the demon

possession that drove her to kill her baby while a Christian

Headmaster's attempt to exorcism a child ensnares a community church

in a lawsuit that pits freedom of religion against a powerful,

Satanic organization (Wikipedia, 2012, para. 2).

Speare, Elizabeth George. (1961). The

Bronze Bow. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Published in English and Norwegian [print, e-book and audio e-book available

through ILL]. Genre Category: Children's Fiction (upper elementary,

middle school) and Historical Fiction.

This Newbery Award-winning bildungsroman, or coming of age, novel wins the praise of evangelical

Christians, who favorably compare it to such classics as to Ben

Hur and The Robe; however, politically correct critics

wish to ban it, believing it unfairly represents first-century

Judaism. While the zealots and religious leaders depicted in the

novel certainly serve as foils to Jesus, Speare also balances these

stock characters with more sympathetic and more rounded ones.

Andrews, Adam and Andrews, Missy.

(2007). The Bronze Bow by Elizabeth Speare: Questions for

Socratic Discussion. The Center for Literary Education. Retrieved

from http://www.centerforlit.com/pdfs/TG05BB.pdf

Questions on The Bronze Bow

address setting, character structure (conflict, plot, and theme),

style, and context while the Andrews offer suggestions for writing

assignments, tests, and a study guide.

The Bronze Bow. (2014).

Christianbook. Retrieved from

http://christianbook.com/the-bronze-bow-paperback/elizabeth-speare/9780395137192/pd/137195

Avenging his father's crucifixion,

Daniel joins an outlaw band that conducts raids on Roman soldiers,

even as he is drawn to the teachings of Jesus, although Christ's

nonviolence message disappoints and confuses him (The Bronze Bow,

2014, para. 1-2). Christianbook readers give Speare's

historical, young-adult novel a five out of five rating, and Booklist

calls it “a dramatic deeply felt narrative whose characters and

message will long be remembered” (The Bronze Bow, 2014,

para. 3).

“The Bronze Bow”: A Critical

Website Created by Parents from Davidson Middle School, San Rafael,

CA. (2007, November). Retrieved from http://www.bronzebow.info/

Three out of five San Rafael school

board members voted to remove The Bronze Bow from the Davidson

Middle School's curriculum based on the recommendations of Marin's

Interfaith council, who criticized Speare historical novel for “its

inaccurate, legalistic portrayal of Judaism that devalues Jewish law

and tradition."

Apparently, post-modern, California

middle school students aren't capable of differentiating fact from

fiction or understanding why the Synoptic Gospels highlighted Jesus'

spirited dialogues with the Pharisees. Thus, Speare's novel along

with such classics as Marrk Twain's Huckleberry Finn falls by

the wayside in the wake of political correctness. Then again, most

contemporary middle school readers will probably only read the Spark

Notes. Whatever happened to teaching rhetoric beginning at the

middle school level?

The Bronze Bow. (2014). Focus

on the Family. Retrieved from

http://www.focusonthefamily.com/parenting/protecting_your_family/book-reviews/b/bronze-bow.aspx

The Bronze Bow targets an

audience of readers age 12 and up, which Focus on the

Family admits “reflects readability and not necessarily content

appropriateness” (Bronze Bow, 2014, Focus on the Family,

para. 1). The novel depicts many of Jesus' miracles as well as much

of his message. However, the leading zealot is totally consumed by

his hatred of the Romans to the detriment of his men (Bronze Bow,

2014, Focus on the Family, para. 2-3).

The Bronze Bow. (2014).

Goodreads. Retrieved from

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/24408.The_Bronze_Bow

Readers of 1,070 reviews give this

historical Young Adult novel 3.91 rating as the gentle lessons of

Jesus begin a gradual, sincere conversion in a young zealot,

replacing his hatred with friendship, loyalty, and allegiance to home

and community. Reviewers thus favorably compare The Bronze Bow

with Lloyd C. Douglas' The Robe (1942) and Lew Wallace's Ben

Hur (1880).

The Bronze Bow. (2014, September

13). Wikipedia. Retrieved from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bronze_Bow

Since Speare's The

Bronze Bow won the Newberry Award for excellence in Children

Literature in 1961, middle school language arts and social studies

teachers have used the book as a supplementary source in parochial

schools, even though some Jewish and Christian critics have

criticized her hostile depiction of first-century Judaism juxtaposed

against an idealized Christianity (Bronze Bow, 2014, para. 1, 8 &

9).

Set in Judea during the ministry of

Jesus, the main characters, Daniel Bar Jarmin and his sister Leah,

see their father crucified, which causes their mother to die of grief

and Leah to succumb to demon possession. Apprenticed to a cruel

blacksmith, Daniel escapes his master, joining a group of young

insurgents fighting Roman rule. After an attack on Romans escorting

political prisoners goes wrong, Daniel realizes that

rebelling against Rome weakens the Jews themselves. Thus, he gradually comes

to understand that Jesus might be the leader for whom they have been

waiting. However, when a Roman legionaire befriends Leah, Daniel's

severe disapproval pushes her back into psychosis. Jesus serves as

the novel's deus ex machina, healing Leah, whereupon Daniel

allows the Roman soldier to call on his sister (Bronze Bow, 2014,

para 2-8).

The Bronze Bow. (2014).

WorldCat. Retrieved from

http://www.worldcat.org/title/bronze-bow/oclc/220950

WorldCat provides an abstract and

several Goodreads reviews of this historical, children's

novel aimed at readers in the upper elementary grades and middle school. A link to multicultural presentation also provides links to

Jewish literature and culture.

Clements, Nancy, Gillespie, Cindy, and

Swearingen, Rebecca. (1994). Readability and the Newbery Award

Winners: How Do They Compare. Yearbook of the American Reading

Forum, p. p. 153-163.

On the Flesch Reading Scale, The Bronze

Bow rates a 85.6 “very easy” reading level while readers consider

it “highly dramatic” (Clements, 1994, p. p. 160 & 163). Most

Newbery Award winners fall into the fifth to sixth-grade reading

level, while The Bronze Bow reads at the fourth to fifth grade

reading level (Clements, 1994, p. 156).

Gornea, Natalie. (2014, January 21).

Review: “The Bronze Bow” by Elizabeth Speare. Around the Bend

of the Book. Retrieved from

http://literaturepurgatory.wordpress.com/2014/01/21/the-bronze-bow-elizabeth-speare-review

Speare's The Bronze Bow doesn't

focus on the life of Jesus Christ, but rather on the consequences of

his mission, as Jesus conversations with Daniel, counseling the young

zealot to love his enemies, thereby reforming a revolutionary who has

had to set aside his revolutionary plans to care for his mental ill

younger sister (Gornea, 2014, para. 3-4). Thus, The Bronze Bow

is a coming of age story in which Daniel learns to comtrol his

impulsiveness as unselfish love and friendship create hope and faith

(Gornea, 2013, para. 6-7).

Kelly, Ina Kroman and Sager, Paul J.

(1970). The Appropriateness of the Newbery Award Books. Children

and Literature. p. p. 49-58. Retrieved from

http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED076967.pdf#page=57

In a survey of ten Newbery Award books

published between 1958 and 1967 reviewed by 500 Spokane students,

only the girls disliked The Bronze Bow, which read at a

sixth-grade level. However, 60 percent of the responders admitted

that the historical novel was among the books that wouldn't be

self-selected (Kelly, 1970, p. p. 53 & 55-56).

Powell, Janet, Gillespie, Cindy, and

Searingen, Becky, et al. (1993). Gender roles in the Newbery

Award winners. Yearbook of the American Reading Forum.

Retrieved from

http://americanreadingforum.org/yearbook/yearbooks/93_yearbook/pdf/11_Powell.pdf

The female characters in the Bronze

Bow follow progressive female roles; for example, when Daniel

refuses to tell Thacia about some murders, she protested, “Why

can't a girl serve Israel too? What about Deborah and Esther?”

(Powell, 1993, p. 105). Progressive women work outside the home,

taking on male-dominated jobs, and are “strong, brave, and

independent” (Powell, 1993, p. 98).

Reinbold, Jean. (2014). Activities for

“The Bronze Bow”. E-How. Demand Media. Retrieved from

http://www.ehow.com/info_12146503_activities-the-bronze-bow.html

Reinbold recommends several activities

that will help middle school students better understand the content

of The Bronze Bow:

- Upon obtaining illustrations of Jewish artifacts and clothing, turn the historical novel into a pay;

- Construct a 3-D map of first-century Israel;

- Go on a Mediterranean picnic, featuring olives, wheat bread, and honey cake;

- Create a diorama of Daniel and Leah's house.

(Reinbold, 2014,

para. 2-5)

Shaw, Jean Duncan. (1968, January).

Children's fiction and American history. Elementary English,

45(1), p. p. 89-94. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/41387675?uid=3739920&uid=2&uid=4&uid=3739256&sid=21104819636997

Many topics originally reserved only

for adults have become subjects for children's literature, including

those found in Elizabeth Speare's The Bronze Bow as children's

and young adult fiction takes on such topics as “the search for

values, problems growing up, travel and understanding people in

foreign lands, and the lives of heroes” (Shaw, 1968, p. 89).

Witan, Sarah. (2013, May 26). The

Bronze Bow (by Elizabeth George Spear[e]). The Newbery Shelf.

Retrieved from

http://thenewberyshelf.blogspot.com/2013/05/the-bronze-bow.html

Asking what it would be like to meet

Jesus, Sunday School teacher Elizabeth Speare wrote The Bronze

Bow, which won the Newbery Award in 1962 (Witan, 2013, para.

1-2). Set in first-century Galilee, rather than Judea as Witan

incorrectly notes, the story centers around the coming of age of a

young zealot, who is so consumed with his hatred of Israel's Roman

overlords that he is also at war with himself until he begins to

understand the teaching of Jesus (Witan, 2013, para. 3-5). Jesus

helps Daniel come to terms with his anger and learn to forgive Witan,

2013, para. 12). Although the books deals with serious themes,

including capital punishment, revolution, and revenge, Middle school

readers will enjoy it if they aren't put off by its length of the

older age of its characters—age 15 to 18. Thus, Witan recommends

the novel as “clean, appropriate, and morally sound” (2013, para.

13). Curiously enough, she makes no mention of the charge that the

book gives a biased view of Judaism.

------------

Booklist's List of Best Religion and Spirituality Books for 2014

Our top 10 religion and spirituality books. (2014, November 14). Read Alert. Booklist Online.

American Library Association's Booklist has picked the top books published on religion and spirituality in 2014. Particularly inspiring is J. Bradley Wigger's picture book, Thank You, God. If you can't find a title, ask a librarian to order it via Interlibrary loan

(http://www.worldcat.org/).

-----------

Buddhist

Buddhist

books Websites. (2014). Budhanet Weblinks. Buddhanet. Retrieved

from http://www.buddhanet.net/l_books.htm

Christian

Denominational

Index of Book Publishers & Periodicals. (n. d.). Christian

Press. Retrieved from

https://christianbookpress.wordpress.com/publishers/denominational-index-of-book-publishers-and-periodicals/

Directory

of Publishers and Vendors. (2001, December 8). Religion Publishers.

Retrieved from http://www.acqweb.org/pubr/rel.html

Religion

Book Publishers. (2014). Publishers Archive. Retrieved from

http://publishersarchive.com/religion-book-publishers.php

Hinduism

Publishers

& Bookstores—Books on Hinduism. (2014). About.com. Retrieved

from http://hinduism.about.com/od/publishersbookstores/

Islamic

(Muslim)

Islamic

books in English and Urdu. (n. d.). Goodword. Retrieved from

http://www.goodwordbooks.com/islamic-books-english.html

Muslim

publishers. (201, April 15). MuslimSotires.Net. Retrieved from

http://muslimstories.net/author-guidelines/muslim-publishers/

Jewish

AJBP

Association of Jewish Book Publishers. (n. d.). Retrieved from

http://www.avotaynu.com/ajbp.html

Rich,

Tracey. (2011). Recommended books and publishers. Judaism 101.

Retrieved from http://www.jewfaq.org/biblio.htm